Leopold I: Problems with Hungary and the Turks

The most urgent problem in the first decades of Leopold’s reign was the expansionist aims of the Ottoman Empire. The situation was exacerbated by conditions in Hungary, where the local nobility opposed the central government in Vienna. It was not until the Turks were defeated at the gates of Vienna in 1683 that the tide turned in favour of Leopold.

After decades of deceptive peace the Ottoman army took up arms once more in the 1660s. However, the Turkish offensive was successfully beaten off by Leopold’s troops at the Battle of Mogersdorf in 1664. This was a brilliant victory, but the geopolitical opportunities resulting from this military success were not pursued any further, very much to the regret of the Hungarian nobility. The Peace of Vásvár, which was very advantageous for the Ottomans, afforded Leopold an urgently needed breathing-space, as a new conflict with France was brewing in the West and he wanted to avoid a war on two fronts at all costs.

This further inflamed anti-Habsburg sentiment among the Hungarian nobility. In the part of Hungary that remained under Habsburg rule – the northern and western regions of the old kingdom together with Croatia – a similar system of governance was to be established to that obtaining in the Austrian and Bohemian Lands, where the dynasty had emerged victorious from its trial of strength with the predominantly Protestant Estates-based opposition. This entailed the suppression of non-Catholic faiths and curtailing the privileges of the aristocratic estates of the Land, something that the Hungarian nobility, steeled by the lengthy wars with the Turks, were keen to prevent.

A group of leading Hungarian and Croatian aristocrats formed, but their conspiratorial machinations were exposed and nipped in the bud. Accused of planning an armed insurrection with French support to throw off the Habsburg yoke, its leaders were executed in 1671 as a warning to their compeers. However, the brutal actions of the government in Vienna had the opposite effect to the one intended, serving merely to strengthen the opposition. Certain members of the aristocracy led by the Transylvanian nobleman Count Emmerich von Thököly started to see a lesser evil in Ottoman rule.

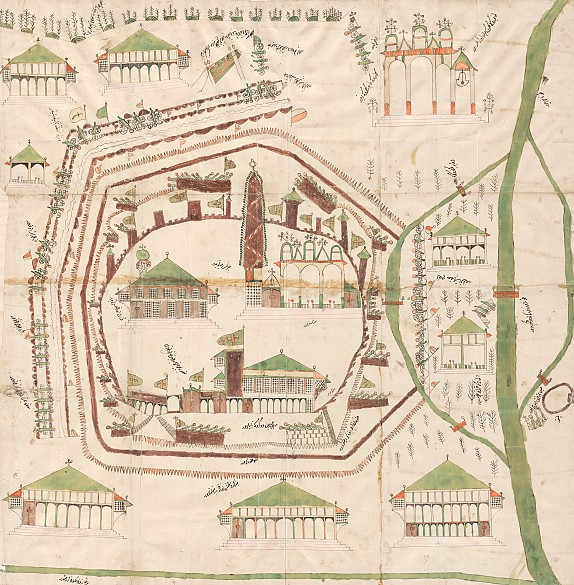

The unstable situation in Hungary was exploited by the Ottomans. A major offensive was started, led by the Turkish Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa. In spring 1683 a huge army gathered to march westwards along the Danube. Its objective was Vienna.

The three-month siege of Vienna in the summer of 1683 became a key event in the history of the Habsburg Monarchy. Leopold and the imperial court had fled westwards, initially to Linz and then to Passau. The city of Vienna was placed under the command of Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg and just managed to hold off the attackers. The Turkish circumvallation was eventually broken by a relief army led by the Polish king John Sobieski and Duke Charles of Lorraine. The army was made up of military units from various parts of Europe with substantial financial backing from Pope Innocence XI. The Turkish army was overwhelmingly defeated on 12 September 1683. The successful joint operation to rescue Vienna in its hour of extreme need was celebrated in contemporary propaganda as a victory of Christendom.