The final decisive battle against Prussia

Hardly any defeat has ever been more painful than that of Königgrätz. And not only for the Habsburgs – the battle was one of the bloodiest of the whole nineteenth century, with thousands of casualties.

On 3 July 1866, the battle of Königgrätz swung the course of the Prussian-Austrian war against the Habsburg Monarchy. Prussia’s victory paved the way to the German question being dealt with along the lines of the ‘smaller German solution’ and to the foundation of the German Reich in 1871. ‘Königgrätz’ became synonymous with the Habsburgs’ defeat.

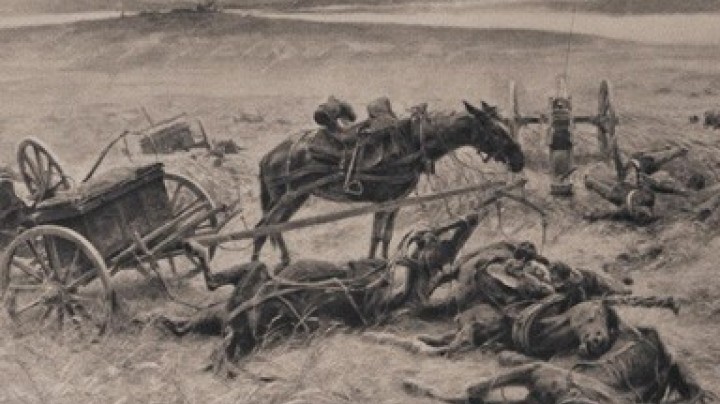

The painting shows the devastation on the evening after the battle. As had been the case in Solferino only a few years before, the numbers of fallen and wounded at the battle of Königgrätz were very high, amongst the highest in any battle of the nineteenth century. The Austrian tactic of the frontal assault featuring a rapid advance towards the enemy went entirely wrong, as the 220,000 Prussians allowed the dense ranks of 215,000 Habsburg soldiers to come close before they opened fire. The losses were horrific – on the Prussian side 9,000 wounded, lost, captured or killed, and on the Austrian several times as many: 42,000. In all, over 7,000 soldiers lost their lives.

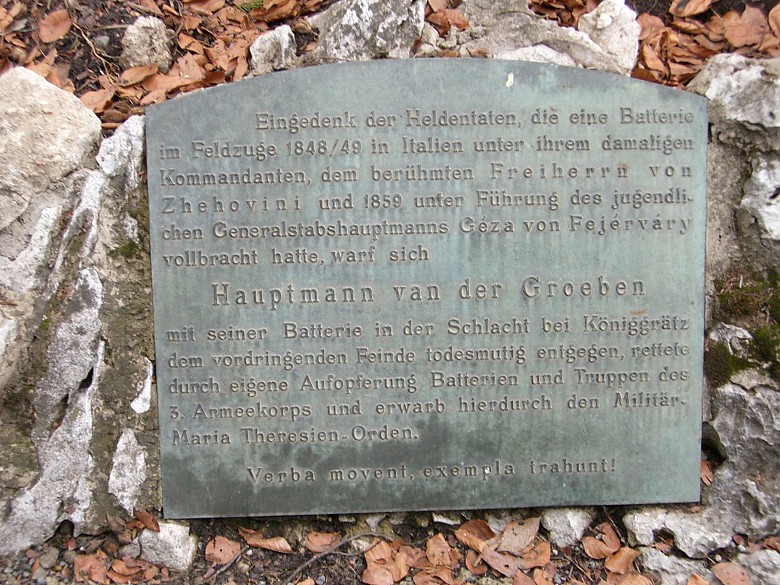

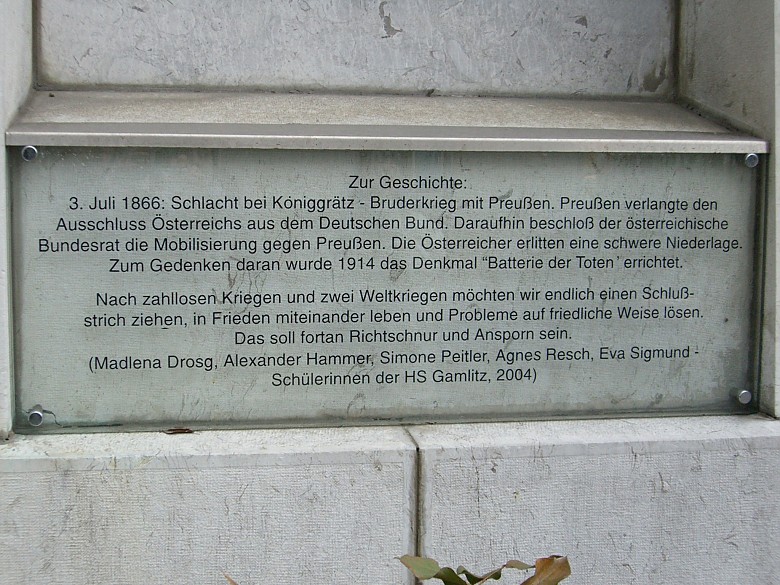

In spite of the devastating Austrian defeat, the battle of Königgrätz was used in monuments – as so many wars have been – for the purposes of glorification. The monument illustrated is just one among many. (In the present case, it is at least accompanied by an additional plaque that presents a more critical view of the events from the present-day point of view.) In such depictions, Königgrätz is represented as the tragic high point of a ‘war between brothers’, the intention being to justify the ruthless deployment of armed forces in order to promote political interests and to relegate the horrors of war to the background.