Elisabeth’s eccentric lifestyle

Elisabeth’s life was shaped by her efforts to prove that her privileged social position was not only due to her rank as empress but also to her personality and individual achievements. Convinced of her uniqueness, at times she felt herself to be superior to other people.

A characteristic that manifested itself in many of her activities was a propensity for extremes. She concentrated all her energies on particular subjects, pursuing them to the point of exhaustion. For example her passion for Greece led her to learn Ancient and Modern Greek and to spend huge sums on building an ideal palace on Corfu called the Achilleion, in which however she promptly lost interest again once it had been completed.

A similar situation pertained with the cult of beauty with which posterity has come to associate her. At 1.72 m, she was unusually tall for a woman of her times. Her height paired with her extremely slender figure contributed to her elegant appearance. She devoted great attention to caring for her flawless complexion and her magnificent head of chestnut hair. Elisabeth’s ideal was that of natural beauty. She used hardly any cosmetics or perfume and did not slavishly follow the latest fashions, preferring understated clothing that was intended to enhance rather than overpower her physical advantages. Although not a classic beauty, Elisabeth made an impression through her aura and presence, which according to contemporaries gave her something ‘fairy-like’. At the same time she hated nothing so much as being gawped at: her beauty was thus an end in itself.

The empress would only let selected artists paint her portrait, with the result that only a handful of authentic portraits or photographs of her exist. The majority of published images are simple retouched variants or photomontages of these authorized portraits. There are virtually no authentic paintings or photographs of Elisabeth in her later years. In the latter decades of her life she made hardly any official appearances and when she appeared in public she concealed her face behind veils, fans or parasols, determined to preserve the legend of her remote beauty at all costs.

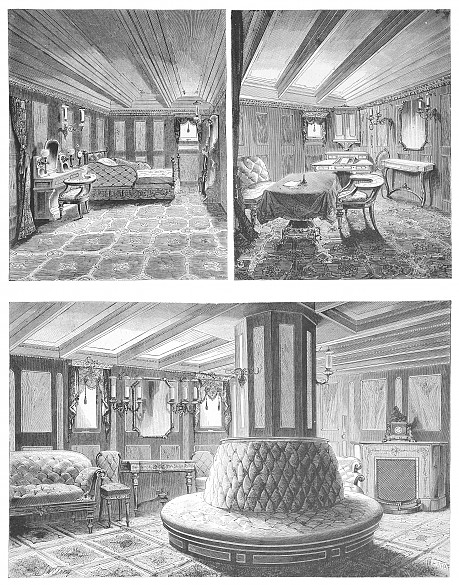

Her enthusiasm for physical exercise also took on extreme aspects at times. A natural athlete, she hiked for hours every day and had exercise rooms installed in her apartments (one of these has been preserved in the Vienna Hofburg), which was highly unusual for a woman in her elevated circles.

The empress was passionately fond of riding, and her capacity for endurance and readiness to take risks made her one of the best horsewomen in Europe of her time. Here too Elisabeth was prepared to spend enormous sums on her ambitions.

At the beginning of the 1880s she was forced to give up riding due to health problems. In compensation she devoted her energies to writing poetry in the style of her idol, the German poet Heinrich Heine. However, this was to remain a secret passion, as she stipulated in her will that her poems, in which she dealt with the world around her in very critical and even scathing terms, should only be published fifty years after her death. Today Elisabeth’s poetic works are appreciated less for their literary qualities than as a personal testament of a historically important figure.