‘Dispensing with all unnecessary pomp’

As in the reign of Maria Theresa, economy and restraint constituted the supreme principles when it came to the decoration of the imperial palaces.

Handwritten instruction from 1807 Franz II (I).The furnishing and decoration of grace-and-favour apartments should be carried out ‘in keeping with propriety, but at the same time dispensing with all unnecessary pomp’.

Wenzel Carl Wolfgang Blumenbach: Wiener Kunst- und Gewerbefreund, oder der neueste Wiener Geschmack, 1825.For many years, it was sought to enhance the exterior of furniture through gilded and bronzed carving … by applying quantities of mounts and ornamentation; however, since 1823 and 1824 this form of ornament has become less common, and Viennese taste has largely proscribed it, demanding in its place a purer form of cabinet-making. Since that time, Viennese furniture has become heavier and more solid, replacing the previous showy decoration with more suitable and nobler forms, with smooth and fluted columns … but [it] also requires more knowledge of draughtsmanship and more painstaking and skilful workers.

Sober restraint was also the watchword under Franz II (I) in matters of interior decoration; courtly magnificence was at most found only in his wives’ apartments. Comfort and functionality were paramount – as in the furnishing of middle-class homes.

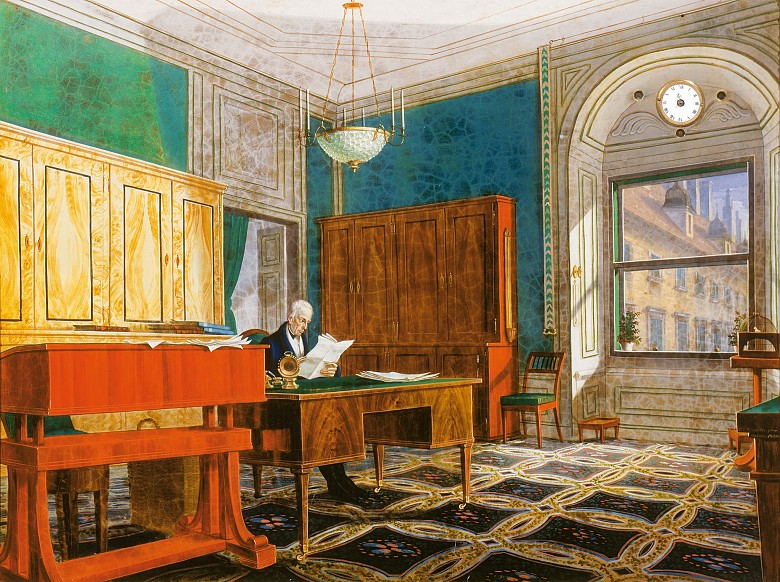

The interiors of the Viennese Court at this time are documented in several watercolour cycles which reproduce faithfully the décor and furnishing of various private apartments occupied by members of the imperial family. They even included views of the imperial bedrooms and water closets, revealing details of ‘Biedermeier’ life at Court. Later on, similar depictions of interiors were commissioned by the middle classes; domestic life increasingly came to represent a general focus of interest.

Various craftsmen such as cabinet-makers, upholsterers and sculptors supplied the interior decoration for the imperial residences. The imperial Court was a major patron and saw itself as a promoter of domestic craft trades. In contrast to the era of Maria Theresa furniture was no longer designed by architects but by craftsmen, who now had access to better training. Joseph II had made attendance at an academy of art a legal precondition for attaining the title of master craftsman. A ban on the import of French goods in 1786 led to relative autonomy and supported development in the various crafts. From the beginning of the nineteenth century craftsmen also received better training in draughtsmanship – facilitating their ability to draw their own designs was intended to promote autonomy and generate formal variety.

The development of new craft techniques led to the emergence of the Biedermeier style in furniture during the nineteenth century. The style of this new furniture was characterized by simplicity, regular forms, beauty and solidity, free from ‘superfluous’ ornamentation. In Vienna, this taste was mainly developed in aristocratic circles and was adopted only hesitantly by the Court and eventually also by the middle classes.