Consumption goes to town – The capital as a ‘city of consumption’

‘One must have one’s little treat,’ could have been the motto of the Viennese, since there must have been a reason for the boom in luxury goods.

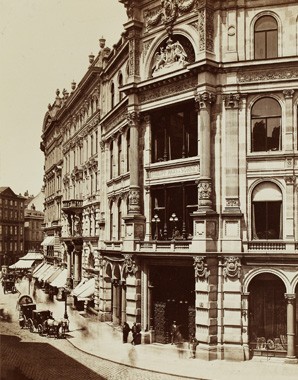

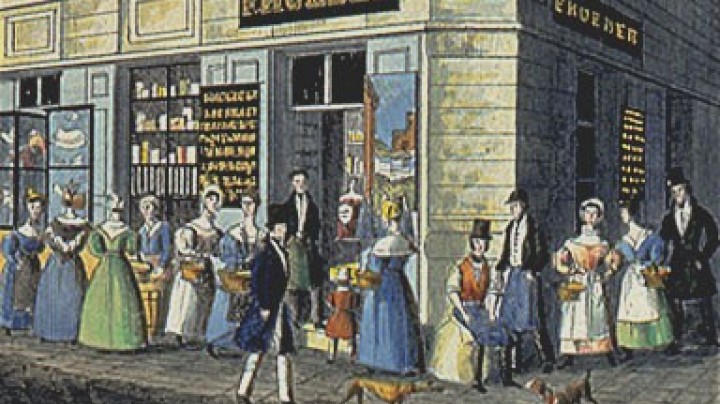

Vienna was not only the capital of the Habsburg Monarchy and the seat of its emperor but was also above all a ‘city of consumption’. It was here that the imperial family and the Court resided and they had to be catered for, even if an ostensibly simple lifestyle had been praised as a virtue of rulers since the years before the revolution of 1848. The Court functioned as a magnet for consumption, because the aristocracy with their extravagant lifestyle were drawn towards it. Since Vienna was the centre of finance, commerce and administration it was here that the highest incomes were concentrated, for example those of entrepreneurs, bankers and senior civil servants from the ‘second tier’ of society. These affluent classes bought expensive and exclusive goods and thus attracted producers and retailers of luxury items. The close connection between the Court and Vienna’s status as a ‘city of consumption’ is made clear by the example of Wilhelm Jungmann & Nephew (founded in 1866), a dealer who had a wide range of silk and wool fabrics on offer: he was appointed a Court supplier and Empress Elisabeth ordered exquisite fabrics from him. Here were two reasons for members of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie to patronize his establishment. There was a demand not only for expensive fabrics but also for high-priced products like the jewellery, furniture and porcelain produced by craftsmen in Vienna. The production of consumer and luxury goods in the city was modelled on the example of cities abroad, and the range of items was so great that Vienna gained a reputation as the ‘city of good taste’. However, the poorer sections of the population also had to be catered for: most of their income went on food, and this makes clear how unequally the possibilities for consumption were distributed.