Anatomical wax models und tobacco enemas – the Josephinum as a training institution for medical students

For the first time practical medical training, using wax models and medical instruments, was provided in the Josephinum, named after Joseph II.

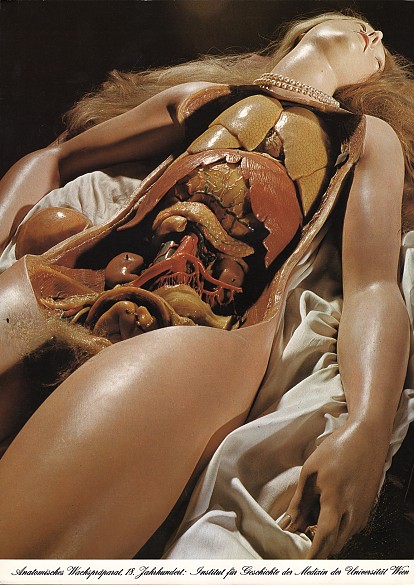

Shortcomings in the medical care of the army persuaded Joseph II to improve medical and surgical training. For instance, field surgeons, who had hitherto only acquired very basic techniques, would henceforth also be trained in surgery. For this purpose, in addition to the medical studies provided in the University of Vienna, the Medical-Surgical Military Academy was opened in 1785 – known for short as the Josephinum. In order to provide students with the best possible education, learning aids such as wax models, medical instruments and a specialist library were provided. The special wax models of human body parts that were produced in Florence for this purpose were intended to provide practical preparation for future anatomical and obstetric procedures. Joseph II commissioned 1,192 such models, with a total value of 30,000 gulden.

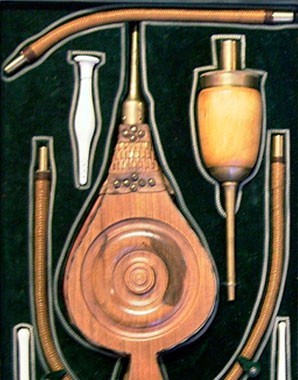

One revolutionary technique was the use of a tobacco enema. This instrument was used for reanimation. Warm tobacco smoke was blown into the rectum with bellows; this, it was hoped, would stimulate the bowel, thereby setting in motion a process of resuscitation. This invention was fully in the spirit of ‘Enlightenment’ philanthropy. But to achieve this it was first necessary to overcome prejudices – such as the belief that touching dead bodies made the living unclean. Maria Theresa’s personal physician, Gerard van Swieten, attempted to eliminate this superstition in his Patent über das Rettungswesen published in 1769, which he wrote of the possibility of using resuscitation to bring back to life people in a state of suspended animation, and those who were drowned, hanged or suffocated. At the same time he sought to counter the myth of vampires that was spreading from eastern Europe. The fear of swollen bodies, which oozed fluid and blood, fed the popular superstition that this was the work of (un-)dead persons who would rise from their graves at night in search of human blood. Bram Stoker’s well-known figure of the vampire hunter, van Helsing – brought to life in the novel of 1897 – was a tribute to van Swieten.