Charles as king of Spain – a monarch on call

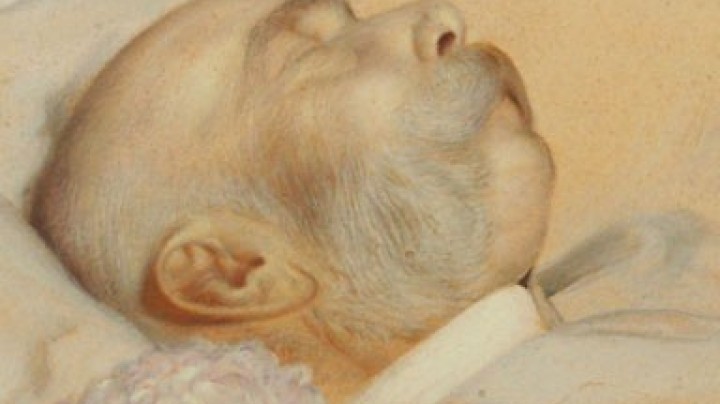

The year 1700 saw the death of King Charles II, the last male Habsburg of the Spanish line of the dynasty. The Austrian branch of the Habsburgs immediately staked its claim to the throne, Emperor Leopold putting forward his younger son, Archduke Charles, as a candidate.

The War of the Spanish Succession that ensued extended across large parts of the continent. The main adversary of the Habsburgs in the conflict over the Spanish inheritance was the ruling French Bourbon dynasty. French diplomats had succeeded in extracting a will from King Charles II shortly before his death which favoured the French pretender Philip of Anjou. The latter was the grandson of the ailing Spanish monarch’s sister, who had been the wife of the Sun King Louis XIV.

Other European states were also involved. Austria was allied to the naval powers of Britain, Holland and Portugal. Britain, the leading power in this coalition against France, was pressing for the Spanish monarchy to be carved up in order to preserve the balance of power. It was imperative that the Spanish territories – Spain proper, the Italian territories under Spanish rule (Lombardy, Sardinia and Naples-Sicily), the Spanish Netherlands and its overseas colonies – should not fall into the hands of a single dynasty, whether Bourbon or Habsburg.

In order to meet the allies’ demands an agreement was concluded to divide the House of Habsburg into two lines. In accordance with the stipulations laid down in the Pactum mutuae successionis of 1703, Joseph, the elder son of Emperor Leopold I, was to continue to rule over the Central European territories and would receive the title of Holy Roman Emperor, while the younger son Charles was designated as ruler of Spain. Not yet twenty years old, Charles was initially little more than a pawn in his father’s Great Power politics.

On his arrival in Spain in 1704 Charles was forced to realize that any hopes he had of rapidly asserting his rule in Spain against his adversary Philip of Anjou were illusory. He found support in Catalonia and Aragon, where the local elites were opposed to the central government in Madrid, but he was unable to bring Castile, the heartland of the Spanish monarchy, under his control for any length of time.

The situation changed drastically when his brother Joseph died suddenly in 1711. Unwilling to relinquish his claim to the Spanish throne, Charles was now the sole inheritor of the Austrian Monarchy and candidate for the imperial throne, which would have meant a huge concentration of power in the hands of one monarch. This was incompatible with the concept of preserving the balance of power in Europe, and the allies consequently withdrew their support from Austria.

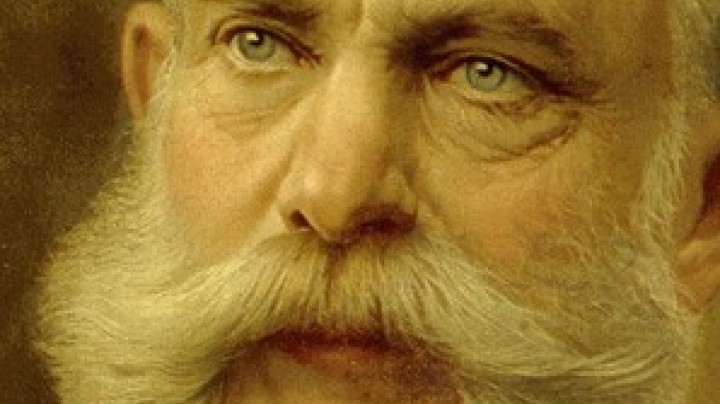

During the course of 1713 Austria’s allies, Britain and Holland, reached a compromise with France without the agreement of Charles, who had no influence over the matter. Charles was eventually forced to accept the result of these negotiations in the Peace of Rastatt in 1714, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession.

The treaty gave the crown of Spain and the overseas colonies to Philip of Anjou, while Charles received the former Spanish territories in Italy (the kingdoms of Naples and Sardinia together with the Duchy of Milan) and the Spanish Netherlands (a region approximately covering present-day Belgium and Luxembourg).

The ‘Spanish dream’, that is, the restoration of the global empire of Charles V, remained alive in his eponymous descendant. For the rest of his life Charles VI was possessed by the idea of being the rightful ruler of the Spanish Empire, a claim that was upheld in the propaganda and art of the Viennese court, in defiance of reality.