Otto, the ‘handsome archduke’

Archduke Otto, called Bolla, is regarded as one of the most scandal-ridden members of the Habsburg dynasty. And yet his life began in the classic fashion for a Habsburg. Otto came from a devoutly Catholic family and embarked on a career in the army, as was the convention for later-born sons of the dynasty.

Born in Graz on 21 April 1865, Otto was the second son of Archduke Karl Ludwig, a brother of Emperor Franz Joseph, and his second wife Maria Annunziata of Bourbon-Sicily. A delicate child, the little archduke was doted upon and indulged by the people around him.

Otto is described as being good-natured and affectionate, in contrast to his dour, withdrawn elder brother Franz Ferdinand, who remained jealous of the younger boy all his life. Gifted, amiable and fun-loving, Otto grew up to become a very good-looking young man.

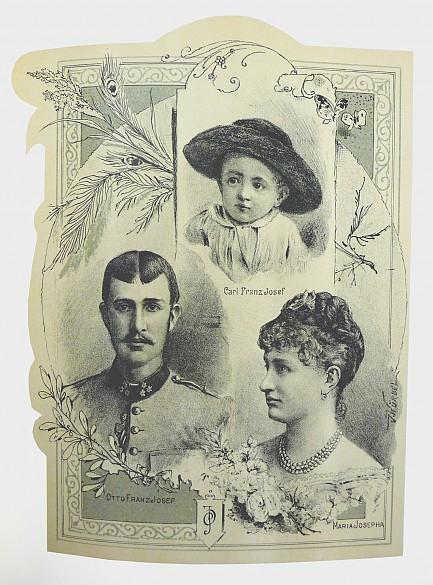

In his choice of bride he complied with Court protocol, marrying Maria Josefa (1867–1944), daughter of the future Saxon king Georg and the infanta Maria Anna of Portugal, in 1886. His wife was extremely devout and content to live according to the dictates and conventions of the imperial court. The union produced the later emperor Karl (1887–1922) and another son named Maximilian Eugen (1895–1952). The latter embarked on a career in the Imperial and Royal Army, and after the fall of the monarchy lived in Switzerland and Germany, where he practised as a lawyer. His descendants live in Germany.

Otto’s numerous extramarital affairs and dissolute lifestyle resulted in scandals which caused outrage both in public life and within the imperial family itself.

One popular and oft-recounted anecdote concerns an incident in which Otto, during an orgy at the Hotel Sacher, ended up reeling down the corridors virtually naked, clad only in a sabre and the Order of the Golden Fleece, eventually running into the wife of the British ambassador, a scandal that was to have diplomatic consequences.

Another scandal led to a question in parliament: a number of high-ranking gentlemen, all members of the imperial family but not mentioned by name, even though it was an open secret that Otto was among them, were alleged to have come upon a funeral procession while out riding and to have jumped the coffin at a gallop for fun. A few days later, the Social Democrat representative who had tabled the question was brutally beaten up by a gang of thugs.

This was all the more embarrassing as Otto was high up in the line of succession. After the suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf only his elder brother Franz Ferdinand stood between him and the throne. The latter suffered from tuberculosis, his weak health making his suitability as a ruler questionable. Otto had been assigned the Augarten Palace in Vienna as a residence befitting his rank and was being groomed for official duties, which his ever-jealous elder brother felt as an affront.

The archduke’s marriage was overshadowed by the incompatibility of character between him and his wife. Maria Josefa drew on her deep religiosity for solace and support in coping with the humiliations and scandals she suffered at the hands of her husband. Otto made his wife’s life a veritable hell: once, after a night spent drinking with his fellow officers, he was only prevented at the last moment from breaking into his wife’s bedroom in order to show his drunken companions ‘a nun’. In the end the marriage was only intact pro forma, a divorce being out of the question. Husband and wife had virtually no contact with each other.

Otto was a bon vivant who had numerous extramarital affairs. Besides the children born in wedlock he also had a number of illegitimate offspring, some of whom he recognized officially, thus ensuring that they were provided for. He had a son with the ballet dancer Marie Schleinzer and a daughter from his long-term liaison with the singer Louise Robinson.

As a consequence of his sexual escapades he became infected with syphilis. At that time there was no effective treatment for this disease, a circumstance that condemned patients to lingering agony. The consequences of the infection in Otto’s case were so severe that he disappeared from public life: his nose became deformed and he had to wear a prosthesis made of rubber. His larynx began to disintegrate, a process that was extremely painful and resulted in an offensive odour from the putrefying tissue. Otto spent his last years in seclusion in a villa in Döbling, a well-to-do suburb of Vienna, looked after by ‘Sister Martha’, the pseudonym used by his last mistress, the operetta singer Louise Robinson, who remained faithful to him to the end. The only remaining contact with the imperial family was his step-mother, Archduchess Maria Teresa, who visited him regularly.

Otto was released from his misery on 1 November 1906, aged just forty-one. He was interred in the Imperial Crypt of the Church of the Capuchin Friars in Vienna.

After his death his widow Maria Josefa emerged from his shadow, surviving him by several decades. When her eldest son Karl ascended the imperial throne she flourished in her role as proud mother of the emperor. She was active in caring for the wounded during the First World War, and eventually followed her son into exile.