Maria Theresa and her reforms

The War of the Austrian Succession had laid bare the weaknesses of the Habsburg Monarchy, revealing it as a Great Power with feet of clay. The antiquated administration of state and army together with the growing economic deficit demonstrated the urgent necessity of reforms.

After the continuation of the Monarchy and the international recognition of Maria Theresa as ruler had been guaranteed by the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, systematic reform of the state administration was undertaken from 1749 under the supervision of Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz (1702–1765).

The Geheime Haus-, Hof- und Staatskanzlei having already been established in 1742 for the spheres of foreign policy and dynastic affairs, the focus was now on the internal administration. The aim was to create a modern and effective state bureaucracy. The administrations of the various different territories of the Monarchy were to be unified and the autonomy of the individual Crown Lands curtailed in favour of a centralized administrative machinery controlled from Vienna.

In order to effect this, the powers of the Estates within the individual Crown Lands had to be limited. The Estates represented the Crown Land in its dealings with the sovereign. However, they were not a truly representative institution in the modern sense; the diets of the feudal age contained only representatives of the nobility, the Church and privileged towns who exercised local dominion over their feudal subjects.

As a consequence of the lack of state administration on a local level the sovereign relied on the cooperation of the Estates in many important areas such as the collection of taxes or jurisdiction. Steps now had to be taken to curtail the monopoly of these feudal overlords on local administration. Special rights and privileges such as the exemption of the nobility and the Church from tax were abolished.

The various different administrative structures in the Crown Lands were harmonized and unified. An orderly administrative hierarchy was established, with new local authorities forming the lowest tier of state administration on a local level. Above these were the administrative bodies of the Land, which were in turn subject to directives from a central authority, the ‘Directorium in publicis et cameralibus’; in terms of modern ministerial bureaucracy this was equivalent to the domain of home affairs and finances.

However, this applied only to the Austrian and Bohemian Lands. In 1750 in a handwritten document Maria Theresa defined the core lands of the Monarchy, which consisted of the Austrian Lands (Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the various territories on the Upper Adriatic as well as Tyrol and the Habsburg Swabian territories) and the Bohemian Lands (Bohemia, Moravia and the parts of Silesia that remained under Austrian rule). The implementation of these reforms proved a lengthy process, but resulted in a strengthening of the core Lands of the Monarchy, which were unified by the administrative reforms. However, the latter did not apply to Hungary with its associated territories, the Austrian Netherlands or Lombardy, in which separate administrations continued to exist.

Another aim was the professionalization of the civil service, with intake of middle-class professionals being increased to replace the aristocratic functionaries for whom leading positions had hitherto been reserved.

In the sphere of military administration the Court Council of War remained in place but other reforms were implemented. A decisive part in these reforms was played by Count Leopold von Daun, on whose initiative the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt was established to train a new generation of officers on the most up-to-date principles. The decisive victory won by the Austrian army at Kolín in 1757 confirmed the success of these changes. In commemoration of this event the grateful empress founded the Order of Maria Theresa, its first recipient being Count von Daun.

Economic reforms were also introduced. These included the abolition of internal tariffs with the goal of joining the individual Lands of the Monarchy in a large-scale economic area with unitary rules. The first statistics, censuses and tax cadastres were introduced, enabling the state to gain an insight into the inner structures of the land so that specific economic measures could be implemented.

One of the most important aims of Maria Theresa’s reforms was to increase the population, as it was thought that a larger number of inhabitants would bring about an economic upswing. An increase in population would also provide more soldiers for the army. One of the demands of this economic doctrine, known as physiocracy, was an improvement in the situation of the peasants, specifically the limitation of obligatory labour for feudal overlords. Sparsely inhabited areas such as the Banat region in southern Hungary were systematically settled with colonists from overpopulated areas in a programme of internal colonization. Although some of these individuals moved on a voluntary basis, others, for example Protestants or social outsiders who were not tolerated by the state in the central parts of the Monarchy, were relocated by force.

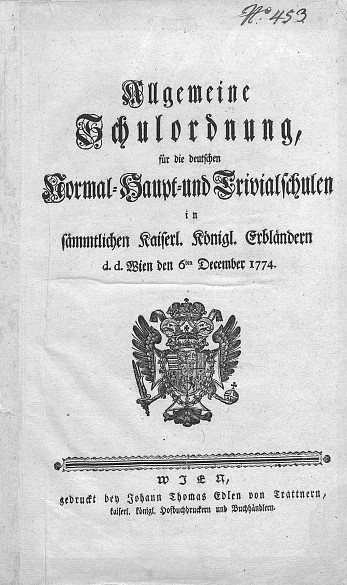

In the educational sector the ‘Studien- und Bücher-Zensur-Hofkommission’, established in 1760, marked the beginning of a centrally administered educational policy. The most well-known of Maria Theresa’s reforms in this field was the introduction in 1774 of compulsory schooling for children in all the Habsburg hereditary lands. This was the first step towards compulsory universal primary education for broad sectors of the population. The actual implementation of this measure was a long-term project, as the necessary infrastructure and teaching staff were lacking. Well into the nineteenth century levels of illiteracy were still high in the Habsburg Monarchy, with strong regional variations.

Within the university system the influence of the Church was curtailed. This development was symbolized by the building of the new auditorium of the University of Vienna (today the seat of the Austrian Academy of Sciences), which was decorated programmatically with allegories of Maria Theresa’s reformist activities in the field of education.