Freelance artists in the sixteenth century

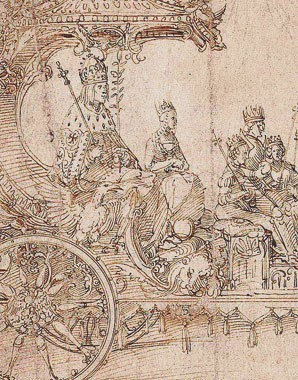

Any princely patron of taste commissioned stately buildings, specifically in the style of the Italian Renaissance. These were mostly executed by artists from the urban centres.

Originating in Italy, the new Renaissance style became the predominant influence on the arts in Central Europe from the sixteenth century onwards. Feudal landowners sought to use artistic commissions to express the power they had attained and in this way to rival the monarch. In Central European cities it was not only the court that issued such commissions; the wealthy patrician class also invested in art.

The arts played a key role in expressing social standing. The Italian Renaissance style was regarded as particularly elegant and its use was intended to signalize the patron’s cultural superiority. Merchants and bankers also fostered the adoption of Italian art. German traders such as the Fugger and Welser clans supported literature and architecture, and had the interiors of their houses magnificently embellished. Their trading relations gave them direct access to Italian works of art, and they commissioned textiles and goldsmith’s work in Italy.

In Austria and Germany artists were counted as craftsmen and were organized in guilds. The latter laid down standards of quality and training criteria, and determined who was awarded the rank of master craftsman, thus effectively controlling the market. As craftsmen, artists also had to pay taxes and fulfil their civic duties. The guilds served primarily as protection from external competition, and thus there were frequent conflicts between guild members and court artists, who were free of such restrictions (‘exempted by the Court’) and often came from abroad.

In contrast to courtly art, art in the cities and towns was subject to market conditions. Some masters subcontracted their commissions to specialists, who completed the work to schedule. However, when there were no commissions to be had, sculptors, painters and engravers encroached on the urban markets – for example, Albrecht Dürer sent his wife out to sell his prints at local fairs. Artists worked not only for the court and the urban patrician class but also for the clergy.

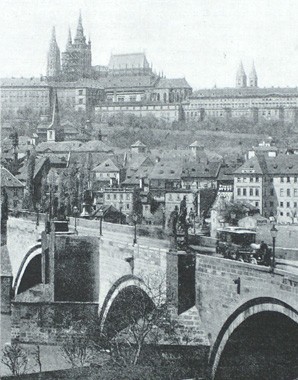

There were close connections between the various places of art production, for example between Prague and Augsburg: Adriaen de Vries, court sculptor to Rudolf II and the painter Joseph Heintz both worked at Augsburg before joining the Court at Prague; Heintz continued to work for the city, even designing public buildings.