Franz II (I): Personality and predilections

Having reigned for 43 years, Emperor Franz II (I) had a profound impact on the empire. A popular ruler in the nineteenth century, today Franz is viewed in a far more critical light on account of his policies.

In the patriotic historiography of the Monarchy the ‘good emperor Franz’ was seen as one of the founding figures of the Habsburg myth. Numerous monuments, the most famous of which stands in the inner courtyard of the Hofburg, celebrate him as the preserver of the Habsburg Monarchy through the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars.

Franz abhorred the idea of popular sovereignty as demanded by the ideals of the French Revolution. Instead he propagated the concept of subjects bound by ties of unconditional loyalty to the dynasty. The emperor acted as the father of his peoples; it was not the state as such but the dynasty that served as the bond between him and his subjects.

His motto Iustitia Regnorum Fundamentum (Justice is the fundament of empires) adorns the Neues Burgtor that was erected as part of the redevelopment of the area in front of the Hofburg, encompassing Heldenplatz, the Volksgarten and the Burggarten. This monument to the Monarchy was built to commemorate the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig which broke Napoleon’s hold on power. The latter had blown up the fortifications in front of the imperial palace before retreating from Vienna, having occupied the city for several weeks in 1809. The building of the victory monument to the troops who defeated Napoleon was intended to obliterate the memory of this humiliation.

Franz’s favourite project, the Franzensburg in the park at Laxenburg, reveals a rather extravagant trait in this Habsburg who otherwise liked to present himself as a citizen-emperor with modest tastes. He spent large sums of money on turning the park into a kind of Habsburg theme park.

Another of the emperor’s favourite places was the spa town of Baden, south of Vienna, where he would stay at the Kaiserhaus on the town square on his frequent visits. The Vienna Woods, beloved of the emperor, are regarded as embodying the love of nature that was so typical of the Biedermeier age.

Patriotic historiography likes to depict Emperor Franz as a staid family man. Numerous anecdotes gave rise to the image of an eccentric character possessed of a dry sense of humour, with Franz appearing as a virtual prototype of the likeable Viennese curmudgeon. Less well-disposed biographers portray Franz as cold, calculating and lacking in emotion.

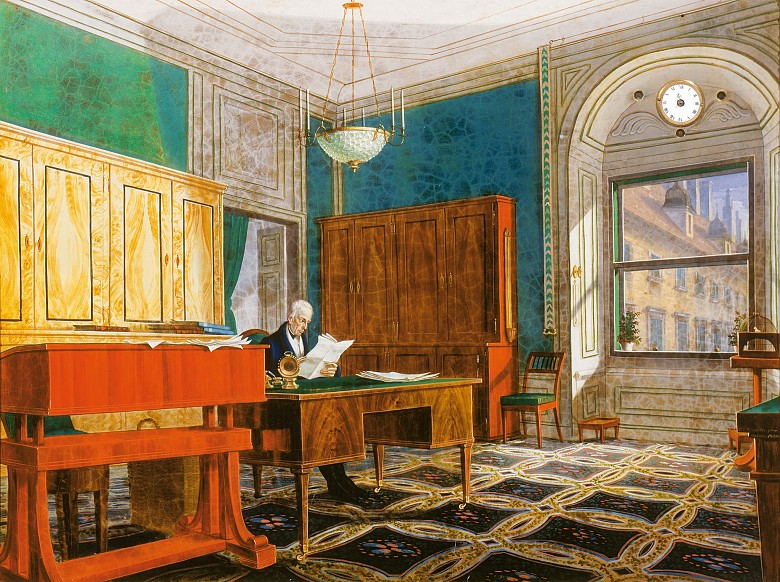

He preferred life away from the public eye. His aversion to pomp and ceremony was not only in keeping with the tenor of the times – the Romantic Age favoured naturalness and simplicity – but was also grounded in his sober personality.